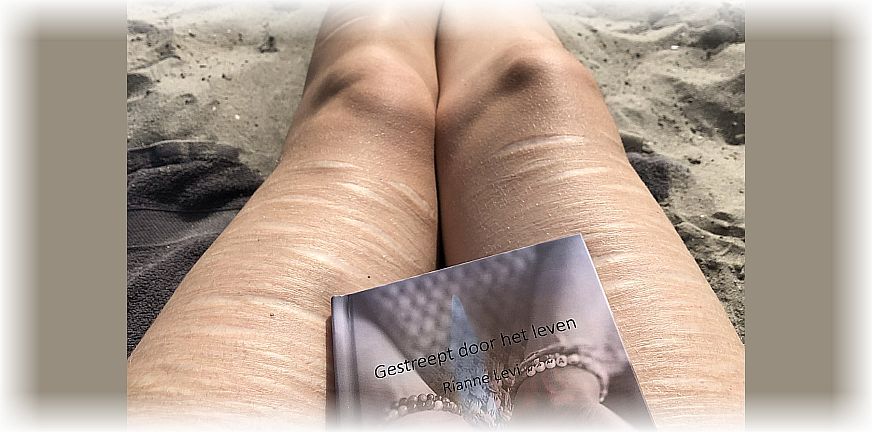

Rianne on self-harm: I’m going through life ‘striped’. I had my doubts about posting the above picture, even though personally, I think it’s beautiful. There was someone who thought it was provocative, and some people may find it shocking. But I need to share something about self-harm, and would like to break the taboo.

It’s a completely different topic to what I normally write about, but I remembered something that happened a long time ago, when I was still breastfeeding. Some people thought you shouldn’t breastfeed in public, because it would be provocative. But I thought: ‘There are billboards all around us, with half-naked ladies on them, and in lingerie shops there are lots of half-naked women on display, which nobody ever mentions.’ So the question is: ‘What exactly is it, that we look away from?’

Anyway, you may work in an Accident and Emergency department or in a Critical Care unit, and occasionally come across self-harm. Is it something that you’d look away from? Do you have an opinion about it? Or are you curious about what it is that makes people want to hurt themselves?

I would like to use Franz Ruppert’s trauma-theory

to look at this issue of self-harm. It can give us an insight into human behaviour. A shocking experience, threat, or stress, can cause a reaction: you can fight your way out, run away from it, or freeze. Generally speaking, the body as well as the mind can recover in peace and unity after a traumatic experience. But if this peace and unity doesn’t materialise, a split can appear. As Dr. Gabor Maté said: “Trauma isn’t your intense experience, but it’s what happens inside you with regard to this experience.” A split appears when the surviving part, does not want to feel the trauma part. It represses, compensates, avoids, controls, projects, and creates illusions. Quite often, trauma causes a broken connection; a broken connection with our bodies, our zest for life, purpose, other people , nature, and the most significant one, a broken connection with our bodies.

If we look at self-harm, it is a survival strategy

to not have to feel this trauma part. It works like this: as a result of our cuts, several hormones are released within the body, stress hormones (adrenaline), but also our bodies’ own pain relieving hormones (endorphins). So the cutting also numbs the body. Cutting is a destructive action, it is actually an assault, but against oneself. It becomes an inner dynamic; when something happens in the outside world that affects the trauma part, it becomes the surviving part and becomes the assailant to itself.

And in the perpetration itself, the following split can appear: feelings of pain, guilt, regret, sadness, and shame, don’t want to be experienced. So they’re being separated from what we’re feeling, because they’re unbearable. The survival strategy to not have to feel that part is that someone doesn’t accept their assault: someone could dissociate, keep their actions a secret, excuse their actions, blame the victim, despise them, or put them in a bad light. By blaming the victim or despising them, an inner perpetrator/victim dynamic is created. A downward spiral, or self-hate.

I’ve regularly heard stories about people not receiving help in the Accident and Emergency department

because the patients would have injured themselves, so it’s their own fault. It’s also been said that people do it because they want attention, and that you therefore have to ignore them. But how many people end up in hospital because of their own choices, like bad nutrition, smoking, drinking, not enough exercise, or dangerous activities like jumping on a trampoline. Should we not help these people because they are partly to blame? The question remains: what are we looking away from? And the answer is quite simple: our pain.

I self-harmed from my 14th till my 20th birthdays. I’m surprised that nobody has ever asked me: “Why do you need to self-harm? What does it do for you?” Or, more importantly: “How awful that the pain you feel inside is so strong that you feel like you have to do this.” Especially this last sentence really validates what is really going on inside your body. Do care providers dare to be present, and silent, when it concerns our pain? Of course, care providers do see different solutions than self-harm, but at the moment they are having to deal with this, your client is not quite there yet. Therefore, it isn’t helpful to suggest different solutions, or judge the patient, or to ignore them, because by doing this you don’t accept the real pain, in that moment. It’s even worse to not help the patient, or to punish them for what they did, because then you’d turn yourself into a perpetrator.

How can we help someone come out of this inner perpetrator/victim dynamic?

I think it would help if we shifted our focus. I often see care providers so fixated on methods, protocols, and dynamics, they forget that there’s a ‘whole’ human being in front of them. A person who knows ‘mental well-being’, but got a bit lost in all the experiences, thoughts, and feelings. But this person is just like all the others, and we can point out to them their healthy part, their own autonomy. So that someone can look at their experiences, thoughts, and feelings, with real curiosity and compassion. In connection and in peace with the care provider, who follows and supports the steps their client takes.

The approach of compassion and curiosity

This approach helps to break the victim/perpetrator dynamic. There’s nothing wrong with people who self-harm, although they may think there is. They are reacting normally to abnormal, traumatic circumstances in their lives. We can appeal to their healthy part, the essence of every human being. What I mean by this is that we can mirror our trust, and be patient and caring. Because this message normally isn’t included in their assortment of experiences. When unity, connection, and wholeness are experiences, it’s possible to experience pain or sadness. And we can use this as the foundation for recognising thought-patterns, and feeling and experiencing emotions. It might help to speak of our parts (healthy, trauma, and survival part), but this is really just a metaphor. The key message is that everybody is essentially ‘whole’, and that we can show this ‘wholeness’ to other people. You may feel broken by everything you’re going through, but all these experiences are part of the human experience. They don’t say anything about you, a person in essence, your worth.

Imagine a fifty pound note, and imagine me wrinkling it. Would you still want it? Or imagine me chewing it, or spitting on it. Would you still want it?

Its worth stays the same, regardless of the circumstances, and people are the same, and we can show this to others.

What a beautifully moving and impressive Blog Rianne. Your word are interresting and convincing. Self-harm is often rather confusing for others and that makes your insights extra important. Thank you!